By Dimensional Fund Advisors

Index additions and deletions are typically a routine affair, but the recent announcement by S&P that Tesla would be added to the widely tracked S&P 500 Index stirred up quite a lot of attention. No surprise, given that Tesla is the largest company to ever join the index and, at the time of its addition on December 18, 2020, became the sixth-largest company in the S&P 500.

On news of the announcement on November 16, Tesla’s stock price jumped 8.2% from $408.09 to $441.61. As shown in Exhibit 1, Tesla then continued to post strong returns, closing December 18 up 70.3% since the announcement. That made the 2.3% return to the S&P 500 Index[1] over that period look meager by comparison.

Exhibit 1: Tesla Daily Stock Price:

January 1, 2020 through December 31, 2020

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

While Tesla’s stock price wowed investors ahead of the company’s addition to the S&P 500, the pattern quickly reversed: The stock climbed 13.9% over the five days ending with its index addition on December 18 yet slumped 4.8% over the subsequent week.[2]

What does this mean for investors? The answer, unsurprisingly, is that it depends.

Indices generally undergo regular reconstitution events during which securities are added or deleted. Index funds, constrained by the objective of maintaining low tracking error versus the index, generally have to mirror these changes by purchasing and selling securities based on the revised index weights.

With over $4.6 trillion in assets tracking the S&P 500 as of year-end 2019, that implies many index funds sought to buy Tesla stock on the day it was officially added to the index.[3]

For passively managed index funds, this lack of flexibility can come at a cost. One way to assess this potential cost is to examine the extent to which index reconstitution events are associated with unusually high trading volume. Abnormally high trading volume is a potential indication that demanding immediacy to trade in such stocks in the same direction may be costly.

We illustrate such abnormal trading volume in Exhibit 2, which compares trading volume in stocks added to or deleted from the S&P 500 on reconstitution day with trading volume in the same stock on days before and after the reconstitution day across reconstitution events over the 2015–2019 period. For the 40 days before and after reconstitution day, we present the average volume for rebalanced stocks as a multiple of the stocks’ volume on the day 40 days prior to reconstitution.

If trading volume on reconstitution day is abnormally high for a rebalanced stock, it would lead to an increase in its multiple of volume traded on reconstitution day relative to non-reconstitution days. Indeed, averaging the volume ratios across all events over the five-year period, we find that trading volume for rebalanced stocks spikes more than 25 times relative to volume over the prior 40 days.[4]

Exhibit 2: Order of the Day

Abnormal Trading Volume in S&P 500 Index, 2015–2019

Demanding such unusually large trade volume can result in price pressure. But this price pressure does not have to manifest itself all on the day of reconstitution. We believe market prices are forward-looking.

Thus, because index rebalances are announced before the reconstitution date and often anticipated before the announcement date, an approach that is constrained to rebalance on the same day as an index may suffer from price pressure well ahead of the reconstitution date. Indeed, our research shows that stocks added to an index tend to outperform their respective indices prior to rebalancing, while stocks deleted from an index tend to underperform.

The remarkable upward march of Tesla’s stock price ahead of its addition to the S&P 500 is consistent with that pattern.

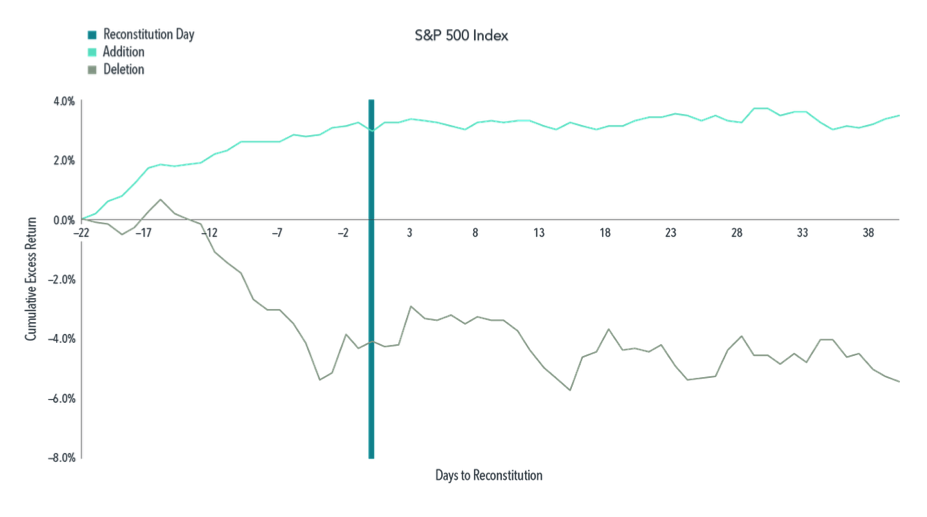

More broadly, we see in Exhibit 3 that the prices of additions (deletions) start to move higher (lower) than those of their index peers one month before the reconstitution day for the S&P 500.[5] This behavior suggests pricing adjustments may be occurring well before the reconstitution day for those indices.

Exhibit 3: Running Start

Average Cumulative Excess Return of S&P 500 Additions and Deletions, 2015–2019

The reconstitution effect is one example showing the lack of flexibility of an index approach, which can leave returns on the table.

While some of these costs can be mitigated by trading on a different date or spreading trading over a few days, we believe an even better approach would be a daily process that maintains a consistent focus on stocks with higher expected returns and spreads turnover across the entire year, with flexibility at the point of trade execution across stocks and quantity. Such an approach allows investors to incorporate information about liquidity and trading costs and avoid the cost of demanding immediacy from the market.

A daily investment process also allows for the incorporation of short-term information about expected returns that is relevant over days or months, such as momentum and information from securities lending fees. Such short-term information cannot be incorporated efficiently if rebalancing happens only once or twice per year. In addition, daily portfolio management can further enhance investment outcomes by maintaining a consistent and accurate focus on the desired long-term drivers of expected returns and continuously balancing tradeoffs between premiums, costs, and diversification.

Footnotes:

S&P data © 2021 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved.

Stock return over the week prior to index addition is from Friday, December 14, 2020, to Friday, December 18, 2020. Stock return over the following week is from Friday, December 18, to Thursday, December 24. Data are from Bloomberg LP, compiled by Dimensional.

Total assets indexed to S&P indices is from Annual Survey of Assets published by S&P Dow Jones Indices, as of December 31, 2019.

Reconstitution events for S&P indices sometimes fall on triple-witching dates, or days on which stock index futures, stock index options, and stock options all expire simultaneously. We examine reconstitution events outside of normal rebalancing dates, and therefore on days that do not overlap with triple-witching dates, and find that stocks added to or deleted from the S&P 500 Index still experience, on average, trading volume 26 times greater on the date of rebalancing relative to the trading volume 40 days earlier.

The initial increase in the gray deletion line is primarily driven by ENSCO PLC, which was dropped from the S&P 500 Index on March 29, 2016, due to an international merger. See “Ensco plc and Rowan Companies plc Merge to Form Ensco Rowan plc, Industry-Leading Offshore Driller,” Business Wire, April 11, 2019.